A Very Rough Draft

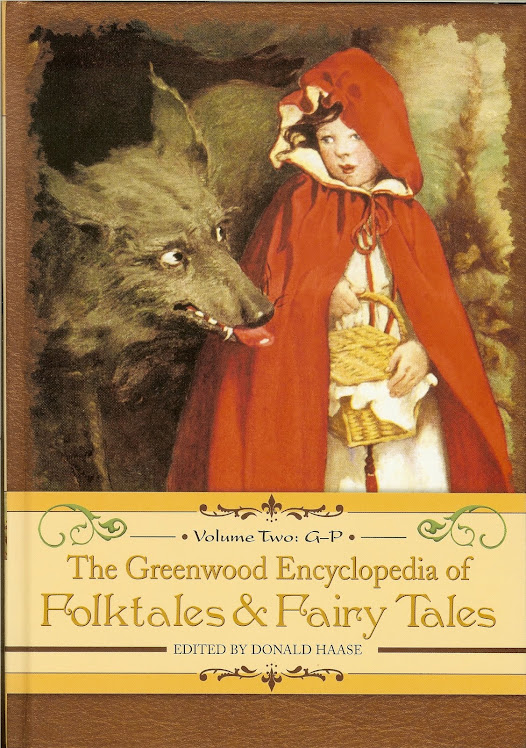

A pivotal work in the fairy tale scholarship for English speakers, The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales will advance the scholarship in unprecedented ways. It is not an anthology, but rather a near-comprehensive reference tool in three volumes. Its editor, Donald Haas, one of the foremost authorities in this field, saw the need for this work when reflecting on the heightened interest in folktales and fairy tales, which has become evident during the last fifty years.[1] This ambitious and well thought-out enterprise has a global, multicultural scope by design. Stories, entry topics and entry authors come from all over the world. The six hundred and seventy entries written by almost two hundred well-known specialists offer readers insights into the foundation of culture and help them explore its essence. Entries cover topics form antiquity to the present. A nine (ten are listed in Vol. I) member Advisory Board of experts, professors and independent scholars, was created to select entry topics based on five basic guidelines and eight pre-determined categories. This key information can be found in the concise, yet complete, introduction (xvi) written by the editor. These determining categories notwithstanding, the encyclopedia presents the topics in alphabetical order, thus making this unique reference tool as user-friendly as any other encyclopedia. The categories: --1. Cultural/National/Regional/Linguistic Groups; 2. Genres; 3. Critical Terms, Concepts, and Approaches; 4. Motifs, Themes, Characters, Tales, Tale Types; 5. Eras, Periods Movements, and Other Contexts; Media, Performance, Movements, and Other Cultural Forms; 8. Individual Authors, Editors, Collectors, Translators, Filmmakers, Artists/Illustrators, Composers, Scholars, and Titles --reflect a multi-disciplinary approach and a global reach.

Whether people live in a primitive culture or in a modern society that takes advantage of all the technological advances of the twenty first century, all find value in reading, listening to, or telling stories. Folktales and fairy tales seem to be at the heart of all civilizations, permeating every aspect of them. No matter age, educational level achieved, or social class, stories infuse everyone’s life throughout the day. They spring up in children’s books, a good novel, a textbook, a television show, a film. The public in general most likely does not know every folktale/fairy tale, its origin, its multiple mutations or possible interpretations, but such in-depth knowledge is not required for enjoyment. Furthermore, enjoyment itself will often make readers curious and eager for knowledge. In The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales Donald Haas offers an incredibly representative resource accessible to students and scholars.

Alphabetically organized for easy access, entries are also extensively cross-referenced, in a simple yet efficient manner: tales, topics, people, motifs, within an article that have their own entry appear in bold face. Entries are actual articles of varying lengths, which, as can be surmised from the above list of categories, cover a very broad range of topics. Most also supply a list of resources for further exploration of the subject, thus giving the reader the impression that the aim is to provide near panoptic coverage. The breadth encompassed by the eight determining categories will surprise even many researchers in the field. Search a little and you will find entries as interesting and as disparate as blood libel, death, forbidden room, feminism, Utopia, Undine, Magical Realism, folktales of Rabbinic Literature, Aztec Tales, Taketori monogatari, to name a few. You will also discover tale authors expected and unexpected: George Sand, Oscar Wilde, Alice Walker, Caroline Stahl, as well as Alejandra Pizarnik, Amos Tutuola, Luisa Valenzuela, Wú Chéng’n en (sixteen century Chinese novelist and poet) and many more. Some of the more interesting entries are those dedicated to basic, well-known tales such as “Cinderella,” “Bluebeard,” and “Little Red Riding Hood.” These entries include information on the earliest form of the tale itself as well as on its many variants and reworking throughout the world, stories, novels, and even films which are often not close to the original tale but which contain many of its prominent features

Entry authors offer informative and often intriguing articles written in a clear, concise, scholarly language, erudite, yet not too technical. Though some articles do contain terms and ideas that may confuse lay readers, these are not the majority and confusion is often just a dictionary or an encyclopedia away. In many cases, the problem is the detailed analysis the author makes and the examples he/she selects. Some of the latter are not as familiar to lay readers as they are to specialists. [an example or two?] In addition, although the use of some acronyms may disconcert those who consult the encyclopedia without reading the introduction and other pertinent information contained at the beginning of Volume I. For example, “AT” and “ATU”, followed by a number appear in a large number of entries. These refer to a system for classifying tales designed to avoid problems caused by the fact that some tales, especially those from oral traditions often do not have a fixed title. Part of the problem disappears once on consults page xxi. If one is even more curious, then a trip to a library is in order since the space limitations prevent this encyclopedia from including more information on this particular manner of classifying tales and their variants.

Combined with the abundant background material provided in every article and the suggestions for further reading, these articles could easily be confused with those found in a journal. In sum, one can easily assert that this encyclopedia offers a wealth of information to scholars, students and the reading public in general. Another pleasant surprise is the rich mixture of black and white photos and illustrations that add interest to many of the articles. These comprise photos of tale authors and other literary figures, reproductions of artistic illustrations for stories --often from previous centuries--, as well as scenes from early and newer films. Older illustrations are particularly interesting since they often reveal the attitude of the artist regarding the content of the story (Find the allusion to LRRH, s/v Perrault???). Although this work has few or no weaknesses, perhaps one would be the inclusion of photos of authors. It just seems not such efficient use of limited space; more illustrations of stories would probably serve the reader better.

Reviewing an encyclopedia poses particular problems, not least of which is how does one approach the task? How does one go beyond superficial comments? How does one give the reader an idea of the quality and range of its contents? How does one go beyond superficial comments about its organization and contents to create an in-depth review? A possibility could be to summarize a good number of entries very briefly, but, again, this procedure would merely touch the surface. However, if the reader keeps in mind the title and focus of the work, one can only hope that he/she will agree that summaries of the entries on two key tales offer a better idea of the breadth and quality of the overall breadth and quality of the contents.No matter what version of a tale we have heard or read as children, we can be certain that it is only one of the original tale's many permutations. Take “Little Red Riding Hood” for instance. Its first version seems to have existed in France [DATE] as "The Grandmother's Tale" which, experts agree, was the tale told before Charles Perrault created his literary version. The original was a quite gruesome tale, which involved a werewolf, cannibalism, as well as some sexual overtones (?). It also presents a resourceful young girl who manages to escape unharmed by tricking the wolf just as he is about to eat her. She asks permission to go outdoors to relieve herself, she ties the string the wolf tied to her ankle to a goat and escapes. According to the author of this entry, Sandra L. Beckett, "Most oral tales have a variation of this scatological happy ending."(583) Variants collected include 241 Asian versions of “Grandaunt Tiger”. The main elements are present in these, even though a tiger (perhaps a beast more common in Asia) replaces the Western wolf.

Throughout its many permutations, an initiatory tale in the oral tradition, a cautionary tale in the seventeenth century, a generic story in the twenty-first century, “Little Red Riding Hood” was and remains a very attractive tale to readers of all ages. Perrault’s version adds the red riding hood, which many scholars interpret as adding sexual connotations. So he keeps the sexual element but omits some of the more offensive (for his time) elements such as the cannibalism, the detailed strip-tease which in "The Grandmother's Tale" takes place right before the wolf gets ready to eat the girl and the scatological trick. Perrault also replaced the feisty, smart girl with a naïve victim, as befits a cautionary tale and added a sexually suggestive moral directed at young girls (584). In 1812, the Grimm Brothers presented this tale as part of German oral folk tradition, though their source was a woman of French Huguenot ancestry. Their adaptation, revised in subsequent editions, became a tale more and more aimed at children. The Grimm Brothers introduced the mother’s admonition not to stray from the path in one of those subsequent versions and the tale, happy-ending notwithstanding (the child is saved, the wolf is killed), remains a cautionary one, focused on warning children about the perils of disobedience. Later on in the nineteenth century, the tale went through further alterations to become a true children’s story and became a generic, sanitized blend of the two literary versions, Perrault’s and the Grimm Brothers’. In its many retellings, as with many other tales, “Little Red Riding Hood” reflects the social and literary preoccupations of the specific time of each retelling. Other permutations of this tale also reflect the times. The story has been told in short stories, novels, poetry, picture books, illustrated books, and, of course, comics. Last, but not least, film and theater adaptations started in 1922 and have continued to thrive until the present.

Another well-known fairy tale, “Cinderella”, can claim to be one of the world’s oldest tales. In her thorough research, Vanessa Joosen, author of the Cinderella entry, found the oldest identified variant to be a story written in China around 850 CE. Although the heroine is helped not by a fairy but by a fish, experts have found in that story many of the elements present much later in the Perrault version of 1697 which is, along with that of the Grimm Brothers, the best known version in the West: the evil stepmother, the royal ball, and the small slipper. Joosen also mentions variants originating in Italy,[2] Japan, Russia, Brazil, and Africa. Demonstrably, the basic story --rags to riches-- lies as well at the heart of novels like Jane Eyre and films like Pretty Woman.

Although close element wise, the two most common versions of this tale, Perrault’s and the Grimm Brothers’, present several important differences. Of those, the most startling is that Perrault created a forgiving Cinderella who allows her stepsisters to marry to noblemen from her husband’s court. He also added two morals, which are quite typical of his time: “...'good grace' is worth more than mere beauty.” and “...one needs a good godmother or godfather to succeed in life.” (202) The Grimm Brothers, on the other hand, let the stepsisters receive a double dose of punishment. First, their mother urges them to maim themselves (cut off their toes and heels so that the slipper will fit). Then, as they walk to church with Cinderella on her wedding day, two doves peck out their eyes. This last punishment makes sense within the tale’s context considering that Cinderella helper is not a fairy godmother but rather some birds living in a tree planted by Cinderella on her mother’s grave.

A highly important aspect of the writing dedicated to this tale --the feminist criticism-- crystallizes (?) in Andrea Dworkin’s 1974 book Women Hating. Here, besides the typical accusation that the tale promotes passivity in girls, the author includes a defense of the stepmother, presenting her as a pragmatic mother who stops at nothing in order to help her daughters succeed in a stratified patriarchal society. Joosen also alludes to retellings for adult audiences such as Barbara Walker’s Feminist Fairy Tales (1996). But, this section on criticism offers much more on the subject. [Not balanced... I need a bit more info.]

Not only is “Cinderella” one of the tales most adapted, modified and parodied, it is also one whose location is often shifted to other times, such as the 1920’s, as exemplified both in the writing and by the fashions and architecture present in the works’ illustrations. Western authors have also located it in places as unexpected as Appalachia. It has also been rewritten using animals for characters: penguins, elephants and even smelly dogs. [Not balanced... I need a bit more info.]

In a separate, four-page long entry, Carolina Fernández Rodríguez addresses the subject of the large number of Cinderella films. This story, she declares, is the one which has most been made into film. In a very comprehensive article, she briefly reviews over forty films. She points out that the story’s success in film originates from the same elements that make its literary retelling so popular: a character saved from a life of insults and servitude only by the actions of her prince, a glorification of romantic love, and a happy ending (marriage). But she also asserts that another reason for the success of this type of films is that “... film versions... are especially targeted at a feminine audience usually trained to accept traditional gender roles as the most desirable ones, ... and offer them a chance to experience, ..., the magic of courtship, of being beautiful and desirable, and of transcending loneliness and poverty.” (205-206) Seeming to contradict herself, she also points out that the industry has disseminated Cinderellas throughout the world, “thus socializing the audience to accept the role model that they are offered.” Such assertions made this reader wonder if the first part (audiences trained to accept traditional gender roles) does not refer to the mothers and the second one to the children with whom they so unwittingly share their vicarious pleasure. Other films alluded to are those like Maid in Manhattan, freer versions where magic is absent but which still feature a character who is lifted from an undesirable social position through the love a man much better off than she is.

Another valuable point made by this author is that judging from the characters’ passive or submissive behavior and the lack of power to articulate their ideas, the Cinderellas of modern films have hardly advanced their lot. With one exception, she points out, they are still victims, unable to speak for themselves unless given permission and they still need to be rescued by their princes. In the one exception, Ever After, Carolina Fernández Rodríguez draws attention to a Cinderella more or less empowered by her love of reading, though she still seems submissive to her prince because although she does refute him, she does so only when he grants her permission. Nevertheless, she is not a passive victim but rather an active protagonist who rescues her prince from some Gypsies and is instrumental in gaining her own freedom at the end of the film. Fernández Rodríguez mentions another instance of how the main undergirding of the story remains constant. She analyzes the film Maid in Manhattan and concludes that despite the complexity introduced --racial and ethnic issues, illegal immigrant standing, and single motherhood-- the paradigm appears intact. In other words, economic status and social class still play a key role and the film adheres to Hollywood’s social code by keeping the female character mostly passive and giving the white man the prerogative to approach and accept the ethnic woman.

NEED a conclusion